Tunnel vision: how Magway could be our deliverer

In the era of the self-isolated and the age of the socially distanced, the prospect of having your weekly shopping deposited by drone or shuttled to you by hyperloop seems less like science fiction and more like a necessity.

Phill Davies, the commercial director of Magway, is uncharacteristically lost for words. “The current situation is…” He trails off. In the background there is the sound of children playing. Like many others, Davies is working from home.

“The supply chain is holding up surprisingly well under the strain. It is. They are doing incredible work.” He pauses again. “But I can’t help imagining how much better it would be with a Magway in place.”

In the era of the self-isolated and the age of the socially distanced, the prospect of having your weekly shopping deposited by drone or shuttled to you by hyperloop seems less like science fiction and more like a necessity.

Phill Davies, the commercial director of Magway, is uncharacteristically lost for words. “The current situation is…” He trails off. In the background there is the sound of children playing. Like many others, Davies is working from home.

“The supply chain is holding up surprisingly well under the strain. It is. They are doing incredible work.” He pauses again. “But I can’t help imagining how much better it would be with a Magway in place.”

Magway is one of the next generation of delivery systems. Along with drones and truck platooning, it has the potential to be as transformative as the creation of the US interstate network under Eisenhower.

The Magway vision

At the moment, Magway is not so much a pipe dream, but a dream about pipes.

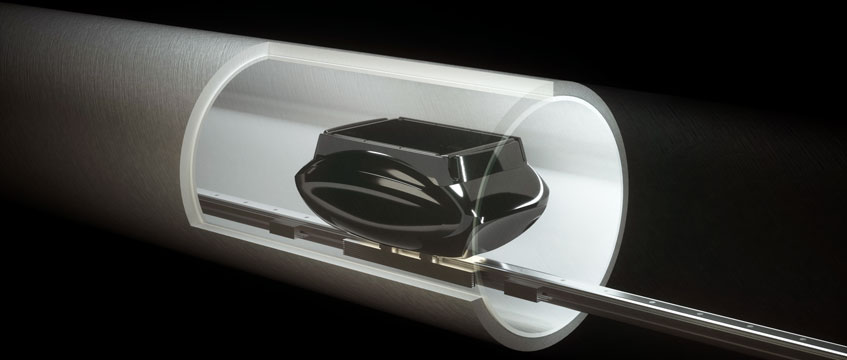

When fully developed, Magway’s pipes will use electro-magnetic forces to drive goods containers through a 3,500km national network.

Distribution hubs will be connected to cities, cities to other cities, ports to hubs, with spurs and spokes burrowing under the earth to link up new developments.

The system would have the capacity to shift 12m tonnes of goods a week with 72,000 carriages moving every hour. At scale Magway could take a third of all delivery vehicles off the roads, reducing C02 emissions by 6m tonnes each year. Users would buy capacity, instead of having to invest in the kit, although some, such as Ocado, are doing just that.

At its core Magway is a hyperloop system, sharing its DNA with Elon Musk’s Hyperloop Alpha project, Spain’s Zeleros and Switzerland’s planned Cargo Sous Terrain. In each, electro-magnetism allows goods carts to be powered through networks of pipes with a minimum of emissions, and potentially at high speeds.

Unlike Musk’s hyperloop, the Magway tunnels will not have to be vacuum sealed and speeds will be a modest 40mph, not the Alpha’s planned 760mph. And unlike Musk, Magway has no plans to shove people down its pipes.

The power to change real estate

“Hyperloop has the potential to have a very big impact,” says Kevin Mofid, Savills’ head of logistics and industrial research. “We could see the emergence of a two-tier market.”

In the short to medium term it is unlikely that any new locations will emerge or new markets evolve, as the pipes are fed into existing parks or new developments on established sites. But a premium could become attached to those sites with the ability to send and receive goods by tube.

“It could be 10% premium or even more,” says Mofid, comparing it to the difference between airside and non-airside space in airports. “It all depends on the operational savings.”

With Magway estimating savings of 50% and more on transport costs alone, that premium could be much higher.

Magway had hoped to have its first commercial projects up and running within the next year. It has been in talks with Heathrow and Gatwick about a series of short links that would have delivered goods such as duty free and packaged sandwiches from consolidation centres to the airport terminals. The airports would get a much-needed infrastructure upgrade, and Magway would have the chance to prove its concept.

Now those plans are in tatters. “All the conversations with the airports were about improving customer experience,” says Davies. “Now they are fighting for survival.” The conversations will still continue, he hopes, but timescales of months look unlikely.

So, what next? “First we will build a bigger demonstrator,” says Davies. “Then we can move onto the commercial projects.” With the airports focused on more existential matters, the big industrial landlords are the best bet. Magway is already talking to several, and Segro is a fan. Big campus projects are also a possibility, with Microsoft and Alphabet engaged in talks.

After that, the real work can begin, with longer routes running along strategic roadways, such as the M1 or M62, to link major distribution hubs. Which routes come to fruition will depend on planning and permissions.

“We have already identified where the best route would be,” says Davies, alluding to a pipe that would run from Milton Keynes to Old Oak and Park Royal. It is, after all, the second-most congested route in the country. “But it is not the simplest.”

Funding the pipe dream

Before Magway can fulfil its dreams of linking the nation with thousands of kilometres of magnetised pipes, it needs to start small.

Currently the only bit of working kit is a small display section, a “demonstrator” showing the linear motors and the basic concept. But soon, pandemics permitting, Davies hopes to have the first commercial projects up and running.

The concept is certainly not being held back by a lack of funding or support. Soon after its genesis in 2017 Magway received seed funding and grants of almost £1.5m, including £650,000 from the government’s Innovate UK.

In February, Magway completed a funding round on Crowdcube to pay for the next phase, with more than 2,000 investors chipping in to finance a working commercial pilot. The concept has captured the imaginations of younger generations, with 45% of its investors aged between 18 and 30. Between them they poured £1.34m into the concept, nearly double the target of £750,000.

But, at a projected cost of £1.5m per mile, it is going to take more than micro-funding from millennials to turn Magway from an intriguing tech to a genuine disrupter.

Davies is confident it will happen.

The key to Magway’s success could be that each part of it can be built independently and sequentially. “Each route is financially viable on its own terms,” says Davies. “The funding is there, as long as we can get the rights and the planning permissions.”

Loops versus drones

Aside from Magway, few new developments in logistics have captured the imagination the way that drones have. From their original military roles, UAVs have become a common feature in daily life, whether being used by surveyors to map sites, medics to deliver supplies, or just for fun. But do the battery-powered bots have the potential to change the face of logistics in the same way that Magway could?

The prospect of having a mini-copter drop your Amazon delivery on your doorstep is tantalising. But according to Alan McKinnon, professor of logistics at Kühne University, it would take nearly 2m drones to replace the vans that make last-mile deliveries, and that would reduce traffic by just 1%.

And while new developments are springing up with dedicated ‘drone landings’ – Halo in Bristol, for instance – the use of drones commercially is already highly regulated and looks set to become even more so.

“Drones definitely have a place,” says Savills’ Mofid, especially in rural areas or for medical deliveries. Potentially drones could be used to transport goods from businesses with more than one warehouse in an area, or at ports. “But they aren’t going to change markets.”

At a time when warehousing and logistics are playing a critical role in delivering essential goods to housebound customers, Magway could provide a compelling solution for the future.

Perhaps the coronavirus crisis will provide the spur to make Magway’s pipe-dream a reality. After all, it took Dwight Eisenhower’s experience of the Second World War for the Interstate network to be built. “And then it took just nine years,” Davies notes.