Broadband: is the UK well connected?

Developers, planners and local and central government make fast broadband a top priority in new schemes. But is the appetite for ever greater download capacity as strong as they think?

Thirty years ago, a sleek steel rail emerged above Detroit, Michigan. The government pumped more than $200m into the Detroit People Mover monorail to provide future-proof infrastructure to a city whose population neared 2m in the 1950s. There was just one problem. The city’s population had fallen to barely above 1m by the late 1980s and it now stands at around 670,000. The People Mover is still there, but the people are not. Across the Atlantic Ocean, the UK faces a similar situation – digitally.

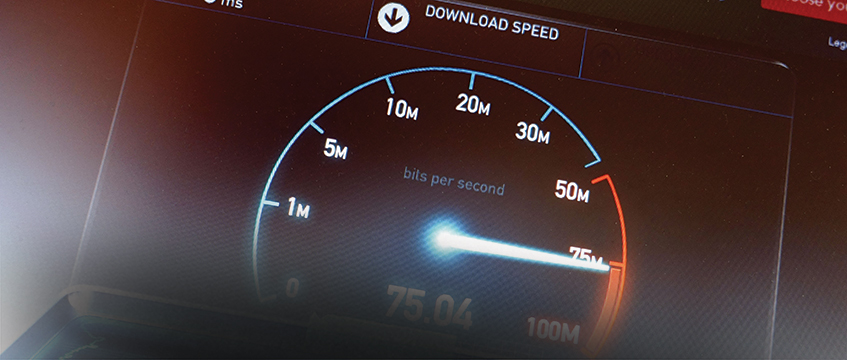

According to a recent study by the Centre for Cities, the UK has a significant gap between digital infrastructure and its use. When it comes to fixed Internet connections, 93% of homes have access to superfast broadband – defined as 30Mbit/s – but only 43% of households have signed up to it. The infrastructure is there, but the interest is not.

Developers, planners and local and central government make fast broadband a top priority in new schemes. But is the appetite for ever greater download capacity as strong as they think?

Thirty years ago, a sleek steel rail emerged above Detroit, Michigan. The government pumped more than $200m into the Detroit People Mover monorail to provide future-proof infrastructure to a city whose population neared 2m in the 1950s. There was just one problem. The city’s population had fallen to barely above 1m by the late 1980s and it now stands at around 670,000. The People Mover is still there, but the people are not. Across the Atlantic Ocean, the UK faces a similar situation – digitally.

According to a recent study by the Centre for Cities, the UK has a significant gap between digital infrastructure and its use. When it comes to fixed Internet connections, 93% of homes have access to superfast broadband – defined as 30Mbit/s – but only 43% of households have signed up to it. The infrastructure is there, but the interest is not.

Meanwhile, businesses in cities have few problems accessing high-speed internet. More than four-fifths of all businesses in inner London, for example, are within 100m of five different fibre optic cable companies’ infrastructure and nearly every single business is within the vicinity of two or three. If a company is prepared to invest in full-fibre in cities across the UK, it can usually make it happen. So what’s the problem?

Simon Jeffrey, policy officer at Centre for Cities, says: “We need to be driving businesses to realise and develop the skills within their organisation to utilise fibre and, by extension, make great use of technology to increase productivity, rather than thinking about intervening on the supply side.”

The government estimates that its superfast broadband programme to roll out high‑speed internet across the country – backed by an initial £530m of public funding – has increased turnover for businesses by a combined £9bn per year since 2012. But given the level of take-up and the opportunities available, Jeffrey argues the private sector needs to step up.

Developers, he says, need to ensure that their buildings are designed to take advantage of existing digital infrastructure. That could mean providing ducting for occupiers to put in the fibre themselves cheaply and easily or ensuring the building is well connected with mobile masts in the area.

Andrew Butterworth, director of sales at Bruntwood – a developer in Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds and Liverpool – says the regions are capable of providing what occupiers need from connectivity. But connectivity is not a guarantee, he says: “We haven’t had one situation where we have had a customer come in and say that connectivity is a problem, but I would like to think that’s as much because we as a landlord and developer are thinking about it right at the forefront.”

Occupiers have different speed requirements so developers need to provide buildings offering that choice. Butterworth says the company works with every major provider from the start of a development to ensure that tenants have no delays in moving in and getting connected. That mentality, he says, has allowed Bruntwood to attract occupiers – including Microsoft – for whom connectivity is a major concern.

Building the sewers – again

Despite the push from the private sector, there is more local and central governments should do. In York, the local council partnered with Sky, TalkTalk and CityFibre to roll out fibre across the area and turn it into the UK’s first gigabit city – capable of delivering speeds of 1,000 Mbit/s. Already, close to 50% of households in York have access to full fibre – compared with just 3% across the UK as a whole. By 2019, York City Council estimates full fibre access will grow to 70-75%.

Roy Grant, the council’s head of information and communication technology, says one of its goals was to reinvent York: “We decided to make York the best connected city in the UK.

“We want to be seen as an R&D platform. If there’s any tech to be trialled, let’s use our connectivity network to trial that. It has changed our job profile.”

The city is now developing its Smarter Travel Evolution Programme, harnessing the fibre network to connect cars to traffic lights. As cars become “smarter”, the network will help the council track transport patterns and reduce congestion across the medieval city. That growing level of sophistication, Grant says, creates a space designed for start-ups and tech firms.

As for the city’s role in all this, Grant says: “The authority has a significant role to play in making this happen. It’s almost like going back to the Victorians putting in the plumbing and the sewers.”

While the Centre for Cities is sceptical about how much central government should invest in full fibre (“Paying to roll out fibre to people who might not even want superfast broadband seems like an interesting use of public money,” says Jeffrey), the organisation does call for government to take steps to enable the private sector to provide better digital infrastructure.

It singles out the Electronic Communications Code, which, through the Digital Economy Act 2017, brought down the rents telecoms operators pay to landowners to install equipment. The Centre for Cities called for the government to review the ECC and assess whether it is a barrier to digital connectivity, owing to landowners becoming less willing to work with operators installing masts or cells.

New buildings

Jeffrey also adds the government should be clear and consistent about the need for connectivity in new buildings: “There should be the requirement for high-quality digital infrastructure in all new development,” he says. “It’s stupid not doing that.”

But Butterworth says there is a good reason for the government to spend public money on connecting the whole of the UK: “They need to support that agenda. The more that can be done to achieve that, the more they are going to help businesses grow and scale and help us win more business and attract more companies into the UK.”

The biggest gaps now are in mobile connectivity. Although the government is investing £200m into 5G – the next generation of mobile infrastructure – current mobile networks are patchy once you leave the city. Just 57% of the UK, by area, has access to 4G from all four operators, according to Ofcom, which explains the incessant complaints passengers have about train journeys being black holes for reception.

Although mobile connectivity leaves much to be desired on an international level, change is happening. 4G coverage has gone from 3% to 57% in two-and-a-half years and Ofcom is looking to award the 700 MHz spectrum band to mobile services in the second half of 2019 to improve coverage. As part of that award, it will require the winning bidder to ensure rural areas across the UK are covered.

Meanwhile, Network Rail is helping address the problem of unreliable connections on trains, upgrading telecoms networks on the TransPennine route between York and Manchester.

It is also a partner in Project Swift, a collaboration with Cisco, ScotRail, IT services firm CGI and Wittos to develop high-speed WiFi services on trains that should deliver up to 300 Mbit/s.

Partnerships like that drive home how far-reaching the interest in connectivity should be. As long as both the public and private sectors understand the need to embrace it, the UK can avoid its digital world becoming the next Detroit People Mover, chugging away year after year in ghostly, abandoned emptiness.

Main image © Jeff Blackler/Rex/Shutterstock

To send feedback, e-mail karl.tomusk@egi.co.uk or tweet @karltomusk or @estatesgazette