The downside of ground rent reform

COMMENT For most residential homeowners, the Leasehold Reform (Ground Rent) Bill will be welcome news.

The bill, which received its first reading in the House of Commons on 15 September, will restrict ground rents on newly created long residential leases. Ground rents will be replaced by a token one peppercorn per year – effectively zero in monetary value.

While a date for the bill’s second reading is yet to be announced, the property market is already adapting. It is becoming the norm that new residential apartment leases are being granted to owner-occupiers without ground rent and with the intention that the freeholder of pure residential blocks will be transferred to a residents’ management company

COMMENT For most residential homeowners, the Leasehold Reform (Ground Rent) Bill will be welcome news.

The bill, which received its first reading in the House of Commons on 15 September, will restrict ground rents on newly created long residential leases. Ground rents will be replaced by a token one peppercorn per year – effectively zero in monetary value.

While a date for the bill’s second reading is yet to be announced, the property market is already adapting. It is becoming the norm that new residential apartment leases are being granted to owner-occupiers without ground rent and with the intention that the freeholder of pure residential blocks will be transferred to a residents’ management company

The removal of ground rent is, on the face of it, good for homeowners, and goes some way in empowering residential leaseholders and making leasehold ownership more affordable.

The proposed legislation does, however, have major financial and operational implications, especially when it comes to the structuring of mixed-use residential and commercial developments.

Potential challenges

Effectively abolishing residential ground rent will remove a major income stream for freeholders. This loss of income could lower the attractiveness of certain developments to investors, forcing some landlords to try to recoup in other areas, with one option being increasing new unit prices.

For mixed-use developments, the lack of ground rent creates a situation where the only regular income stream is from commercial rent. This may have an impact on the relationships between landlords, commercial tenants and residential leaseholders.

The potential legislative changes also pose significant challenges for mixed-use developments when ascertaining which of the three parties will be the best long-term owner of the freehold, considering the different interests and financial obligations.

While it is an increasingly common option for pure residential developments, transferring the freehold of a mixed-use building to a residents’ management company can be complex.

Thought must be given to how well-equipped a residents’ management company will be to oversee a mixed-use development, including its ongoing maintenance and service charge recovery. This is without even considering operating a robust sinking fund or ensuring a building remains compliant in a rapidly changing regulatory landscape, with key focuses including fire safety, for example.

By taking on this responsibility, residents’ management companies will be placed under an extra administrative and legal burden, with many inevitably having to require additional professional help. The result of which may be a Catch-22 situation, with residential leaseholders escaping the financial burden of ground rent, but in the process finding themselves having to increase service charges to pay for the additional support needed to help manage a mixed-use development.

A dilemma for landlords

In response to these challenges, the easy option may be to look to landlords to ensure the successful management of mixed-use developments – considering this has often historically been the case.

However, with the bill effectively wiping out a key income stream for mixed-use developments, some landlords may be reassessing whether being a freeholder is still viable. This may give rise to an increasing number of non‑professional landlords stepping in as freeholders on mixed-use buildings, despite not having a track record in this area.

Landlords must consider the implications of remaining a freeholder without ground rent income, in the knowledge that, if not managed correctly, a building’s long-term value could be impacted – for example, if regular repairs and maintenance fail to take place or are not of the desired standard.

Looking ahead

Some in the property sector may be questioning whether the legislation – in its current form – is a case of fixing one problem and creating another. Either way, with the bill passing through parliament, it is critical that landlords, residential leaseholders and commercial tenants prepare for the changes.

Careful thought must be given on every new mixed-use development to ascertain the best long-term owner of the freehold and long leasehold interests.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution. Each mixed-use development must be treated individually – considering that they can range from a block of 10 flats, with a small coffee shop on the bottom floor, to a 50-storey city-centre tower with commercial units, office space and homes.

Before entering any agreement, residential leaseholders, landlords and commercial tenants must understand the evolving requirements of being a freeholder and seek professional guidance to help identify who is best equipped to take on the role.

Many of the issues outlined can be resolved by structuring legal agreements effectively at the outset, before then seeking professional help from managing agents on a building’s upkeep and operations.

The legal sector, in particular, has a key role to play in helping others navigate these changes and no doubt will step up to ensure the ongoing safe, viable delivery of mixed-use developments in the UK.

Melissa Barker is a real estate partner at Shoosmiths

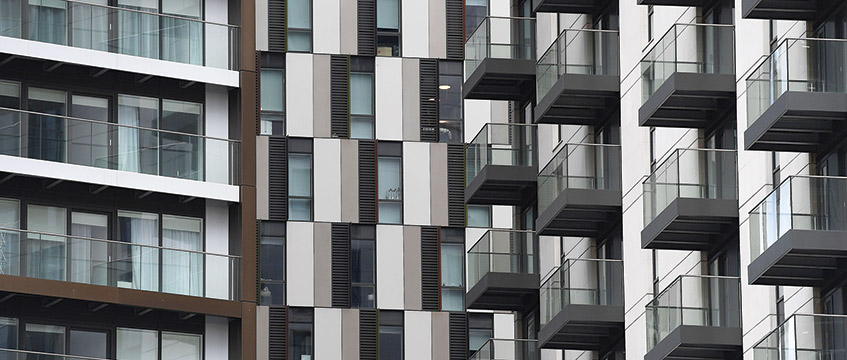

Image © Andy Rain/EPA/EFE/Rex Shutterstock