Back to Basics: Squatters’ rights

Jessica Parry goes back to the drawing board on adverse possession.

Adverse possession is a way in which someone can acquire legal title to land they do not own. It generally applies where someone treats the land as if they own it over a long period of time (usually 10 or 12 years), without the owner’s permission.

This means that someone who goes onto a property as a squatter can eventually become the legal owner. This is why the law of adverse possession is sometimes referred to as “squatters’ rights”.

Jessica Parry goes back to the drawing board on adverse possession.

Adverse possession is a way in which someone can acquire legal title to land they do not own. It generally applies where someone treats the land as if they own it over a long period of time (usually 10 or 12 years), without the owner’s permission.

This means that someone who goes onto a property as a squatter can eventually become the legal owner. This is why the law of adverse possession is sometimes referred to as “squatters’ rights”.

Adverse possession can seem a strange concept: if you steal someone’s land for long enough, the law will eventually give it to you. The owner must “use it or lose it”? It all sounds a bit like legally sanctioned theft. The principles behind adverse possession are to ensure that land is put to good use, and to create certainty in respect of title.

When the Land Registration Act 2002 was introduced, the case for adverse possession based on certainty of title held less force for registered land. Adverse possession did not sit well with the fundamental principle of the land registration system that the register would be conclusive as to the owner’s legal title. As a result, the 2002 Act brought in a new adverse possession regime, which has made it more difficult for squatters to acquire registered land by adverse possession. This regime is generally referred to as the “new rules”.

The “old rules” apply to registered land where the squatter had been in possession for 12 years before 13 October 2003 (when the 2002 Act came into force) and to unregistered land. The new rules apply to registered land where the period of possession relied on ended on or after 13 October 2003.

Essential requirements

The essential requirements are the same under the old rules and the new rules. The squatter must have had:

Factual possession of the property, with the intention to possess;

To the exclusion of all others;

Without the owner’s consent.

Possession means “an appropriate degree of physical control”; the squatter must have possessed with the intention to “exclude the world at large, including the owner with the paper title” (Powell v McFarlane [1977] 3 WLUK 188).

This does not necessarily mean that nobody else can have “used” (rather than possessed) the property during the relevant period. It essentially means that the squatter must have dealt with the property as an occupying owner might have been expected to deal with it, and no-one else has done so.

Whether a person has had a sufficient degree of control of the land is a matter of fact. It depends on all the circumstances, in particular the nature of the land and the manner in which such land is usually enjoyed.

Years of factual possession

Old rules: 12 years.

New rules: 10 years – this is 10 years up to the date of the adverse possession application or the eviction date (where the squatter was evicted, other than under a possession order, in the six months before the application).

Is a Land Registry application required?

Old rules: No. For unregistered land, 12 years’ adverse possession effectively extinguishes the true owner’s title (section 17 of the Limitation Act 1980). For registered land, after 12 years’ adverse possession, the land is held by the paper title owner on trust for the squatter (section 75(1) of the Land Registration Act 1925). The squatter can apply to the Land Registry to be registered as proprietor but does not have to do so. Any action by the true owner to recover the land becomes statute-barred after 12 years (section 15 of the Limitation Act 1980).

New rules: Yes. The 10 years’ adverse possession alone does not affect the owner’s title. After 10 years, the squatter will be entitled to apply to the Land Registry to be registered as proprietor. The Land Registry will notify the registered owner (and other relevant parties) and consider any objections first. The squatter will only acquire legal title by adverse possession if/when their application succeeds.

Can the registered owner object to the squatter’s application?

Old rules: No. Although, the owner may dispute whether the essential requirements for adverse possession have been satisfied.

New rules: Yes. The registered owner can serve a counter-notice to the Land Registry objecting to the application. This might be on the grounds that the squatter does not meet the essential requirements. In addition, the registered owner can object on the basis that the squatter cannot satisfy any of the conditions in paragraph 5 of Schedule 6 to the 2002 Act.

Additional hurdles for the squatter to overcome?

Old rules: No.

New rules: Yes. If the registered owner insists, the squatter must also satisfy one of the conditions. In summary, these are:

Estoppel;

The squatter has some other right to the property; and

Reasonable mistake as to boundaries (see box, below). If the squatter cannot satisfy any of the conditions, their application will be rejected.

Conditions

The conditions are additional hurdles that a squatter must overcome under the new rules, if the true owner insists.

■ Condition 1 — Estoppel

The squatter must show that:

(a) it would be unconscionable because of an equity for the squatter to be dispossessed; and/or

(b) the circumstances are such that the squatter ought to be registered as the proprietor. To establish that an equity has arisen, the squatter would need to show that:

(i) the registered owner encouraged or allowed the squatter to believe that they owned the property;

(ii) the squatter acted to their detriment in this belief; and

(iii) it would be unconscionable for the registered owner to deny the squatter the rights they believed they had.

■ Condition 2 — The squatter has some other right to the property

The squatter would have to prove that they are entitled to be registered as proprietor based on some reason other than their adverse possession. This may cover a situation where the squatter had contracted to buy the property and paid the purchase price but had never taken a legal transfer.

■ Condition 3 — Reasonable mistake on boundaries

Four elements must be established:

(a) the land to which the squatter’s application relates must be adjacent to other land that belongs to the squatter;

(b) there must not have been any determination of the exact boundary between the disputed land and the squatter’s own adjacent land;

(c) the squatter (and any predecessor in title) must have reasonably believed they owned the disputed land for at least ten years up to the date of the application; and

(d) the disputed land must not have been registered more than one year before the date of the application.

Further application by squatter two years later?

Old rules: N/A.

New rules: If:

1. The Land Registry rejects the squatter’s adverse possession application following a counter-notice and none of the three conditions were satisfied; and

2. the squatter remains in adverse possession for two years after their application was rejected,then the squatter can re-apply. The squatter will then be entitled to be registered, except where:

(i) the squatter is a defendant in possession proceedings;

(ii) there has been judgment for possession against the squatter in the last two years; or

(iii) the squatter has been evicted pursuant to a judgment for possession. This means the registered owner has two years to regularise the position, or they risk losing the property to the squatter.

Summary

The rules surrounding adverse possession are complex.

Whether the old rules or new rules apply depends on whether the land is registered and the period of adverse possession relied on by the squatter.

Whether the acts relied on by the squatter are sufficient to show they have acted as an owner depends on the nature of the land in the question, and the way that land would normally be used.

Each case really must be considered on its own facts, and the relevant evidence carefully assessed.

True or false?

■ A squatter can rely on previous squatters’ periods of adverse possession?

True – generally, a squatter can rely on previous squatters’ periods of possession, provided that the total period is the requisite 10 or 12 years.

■ In relation to open land, this must have been enclosed (for example, by fencing) in order for a squatter to establish adverse possession?

False – although fencing is indicative of physical control, it is not conclusive one way or the other regarding adverse possession. Open land which has not been fenced can still be acquired by adverse possession. For example, in Redhouse Farms (Thorndon) Ltd v Catchpole [1977] 2 EGLR 125 shooting over a large area of land was sufficient; and in Roberts v Swangrove Estates Ltd [2008] EWCA Civ 98, the acts relied on by the squatter were fishing and dredging the river bed.

■ Repaving a driveway can be enough to prove the essential requirements for adverse possession?

True – in Thorpe v Frank and another [2019] EWCA Civ 150; [2019] PLSCS 35, the Court of Appeal held that repaving a driveway in front of a semi-detached bungalow was sufficient. Even though the repaving works only lasted two weeks, it was something only an owner would do.

Jessica Parry is a partner at Brabners

Next time in Back to Basics, Andrew Rogers gives readers the lowdown on dilapidations

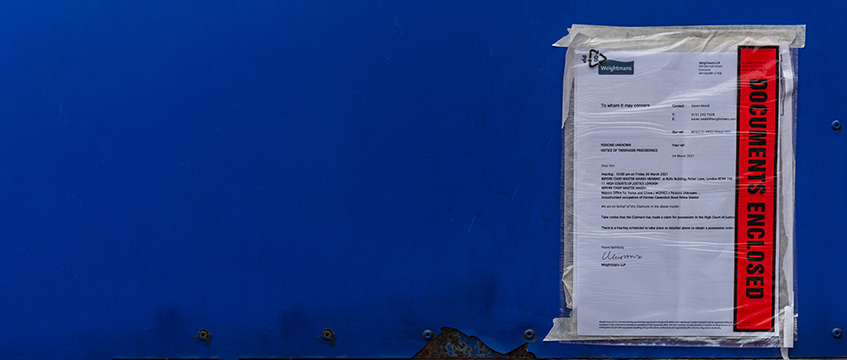

Photo © Guy Bell/Shutterstock