When artists collaborate with developers

The link between an electronic music DJ and the property industry is not immediately apparent. Or eventually apparent for that matter. At least not without a fair deal of explanation.

That is where James Lavelle comes in. A renowned DJ who produced the soundtrack for the film Sexy Beast and has reworked tracks for artists including The Verve, Massive Attack and Beck, he has now turned his attention to property as he embarks on a project that involves creating physical spaces for subcultures.

His latest exhibition, Daydreaming with UNKLE (named after his band), will open at Allied London’s 1.2m sq ft mixed-use Leeds Dock this weekend. The developer’s hope is that supporting a show put on by such a well-known artist will boost awareness of the scheme.

The link between an electronic music DJ and the property industry is not immediately apparent. Or eventually apparent for that matter. At least not without a fair deal of explanation.

That is where James Lavelle comes in. A renowned DJ who produced the soundtrack for the film Sexy Beast and has reworked tracks for artists including The Verve, Massive Attack and Beck, he has now turned his attention to property as he embarks on a project that involves creating physical spaces for subcultures.

His latest exhibition, Daydreaming with UNKLE (named after his band), will open at Allied London’s 1.2m sq ft mixed-use Leeds Dock this weekend. The developer’s hope is that supporting a show put on by such a well-known artist will boost awareness of the scheme.

And Lavelle is using the tie-up as an opportunity to support his theory that subcultures – whether graffiti, hip-hop or even collecting Star Wars figurines – need a home.

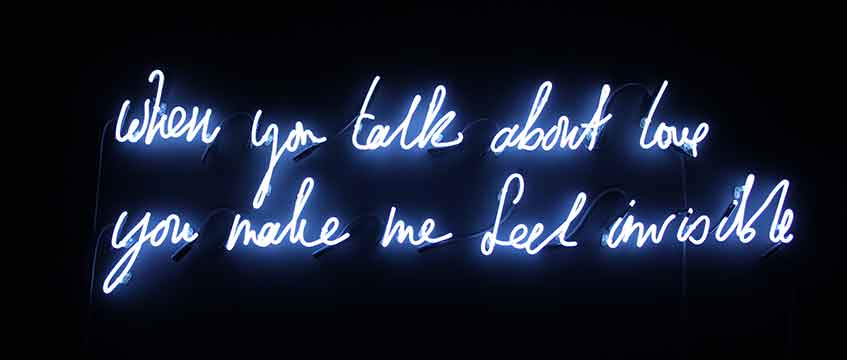

The artist will take over a vacant unit at the development for the two-day show to create an immersive experience featuring virtual reality installations and counter-cultural artefacts.

The benefits for Lavelle are clear: a platform to display his work and market his new album. But how much impact is this sort of event likely to have on the wider urban landscape? Could collaborations between developers and artists such as Lavelle fuel a new wave of creative placemaking?

And how much real value is there to be made in letting space – vacant or otherwise – to showcase what Lavelle refers to as “cultural undercurrents”.

The power of urban spaces

“Urban spaces are very synonymous with a sort of culture that I grew up on, like graffiti and hip-hop,” says Lavelle. “So the place where the exhibition is happening in Leeds is a great environment to display the work.

“It fits the work – it’s not Picasso – it’s street art, it’s coming from street culture. It has that kind of anarchic thing about it. So I think the idea of being able to go into unusual spaces is amazing.”

The “Daydreaming with…” art exhibition series, which has been up and running since 2010, matches pieces of artwork to music tracks to create a multisensory experience. Lavelle’s inaugural exhibition in London recently attracted 5,000 visitors over four days; he has subsequently put shows on at the world-renowned Soho street art gallery Lazarides, W1, and Somerset House, WC2.

And now he is raring to make his mark in the regions. “What’s exciting about Leeds is that it’s a much bigger space,” he says. “So it will be it a different sort of environment.”

On the real estate side, creating physical spaces for subcultures is not new for Allied London. The developer has a track record of collaborating with artists and quirky occupipers to put schemes on the map – starting with the F&B sector. In 2011, when it did its first pop-up at Spinningfields in Manchester, using a slightly quirky, underground occupier as a drawcard was key to building up footfall.

“It was really hard to get people there at first,” says Allied London head of brand & marketing Phil Dawson. “Even the taxi drivers didn’t know where it was.” It was inviting the then little-known Alchemist bar group to open in the area that helped turn things around, he says, and before long, people were queuing round the block to experience the now-famous smokey, old-fashioned cocktail.

“It’s usually a number of little things like that which makes a place,” says Dawson. “You can’t just build something and people will come, as Kevin Costner says in Field of Dreams. You need to grow culture and win the audience’s trust. So through placemaking, people will recognise that you’ve got a lot of passion and authenticity.”

From food to digital art

Now the developer has moved on from offbeat food and beverage offers and is focusing on using digital art to create immersive experiences as a way to bolster placemaking.

“You can work with artists who have these beautiful pieces of art that are immersive and interactive and engaging for all ages,” says Dawson. “And because they are digital you can work with them to merge the work with the location or brief.”

Allied London worked with the Leeds Business Improvement District, one of the creative forces behind the Leeds International Festival, to co-ordinate Lavelle’s UNKLE exhibition with the Leeds Waterfront Festival to make it a citywide cultural weekend of events. It follows hot on the heels of another cultural event commissioned by the developer at Leeds Dock earlier this year: local artists Squidsoup created Light Water, Dark Sky. This digital art installation comprised 6,000 individually programmable lights, which pulsate and change colour to give the impression of moving water, floating on a pontoon.

It was this installation, says Dawson, that highlighted just how powerful cultural shows can be when it comes to raising awareness around a new scheme, getting people down to the development and spreading the word on the developer’s behalf.

“A lot of people who came down for the art and culture are the business leaders or employees of some of the people who have taken units,” he says.

Future collaborations are on the cards with Lavelle, who is eyeing the historic Allied London Old Granada Studios in Manchester as a possible next location. With the studios’ impressive cultural heritage, which includes the first TV appearances of the Rolling Stones and the Sex Pistols, it’s easy to see why it’s an appropriate location. “There’s that swagger to the North that James has as well,” Dawson says.

Swagger indeed. It turns out that Lavelle himself is not actually aware of the concept of placemaking. Not only that, he claims not to spend any time or creative energy worrying about how developers could be better at collaborating with artists.

Once given some thought, however, he does concede that the relationship needs to be worked on for the benefit of both parties. “The problem with property is that when an area becomes cool, like Soho, it becomes a profitable environment for developers to work in rather than an artistic hub,” he says. “And I think there has to be a balance in the way that works, in order to retain the soul of the environment. There’s a line that has to be drawn.”

Sounds like collaboration is on his mind more than he might like to admit. Perhaps this realisation will be the key to stronger, more immediately apparent links between future generations of electronic music DJs and the property industry.

To find out more about the exhibition, click here

To send feedback, e-mail Louisa.Clarence-Smith@egi.co.uk or tweet @LouisaClarence or @estatesgazette